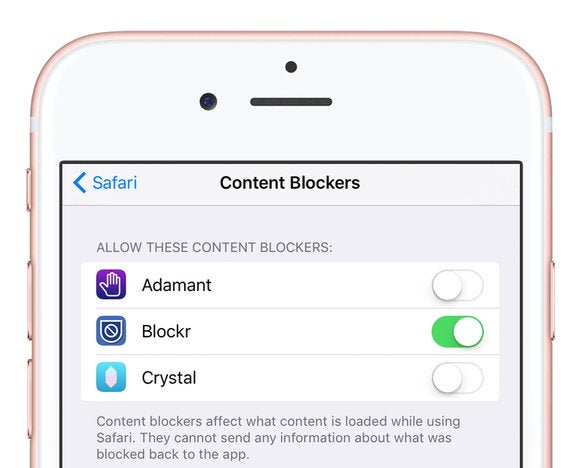

- Roadblock 1 5 9 – Content Blocker Safari Settings

- Roadblock 1 5 9 – Content Blocker Safari Yahoo

- Roadblock 1 5 9 – Content Blocker Safari Extension

Roadblock's app and modern Safari extension work together to provide a unique experience. You can use the extension to block and hide content visually, change the active profile, turn blocking on or off, add custom rules, and view the count of blocked resources.

- Content Blockers are app extensions that you build using Xcode. They indicate to Safari a set of rules to use to block content in the browser window. Blocking behaviors include hiding elements, blocking loads, and stripping cookies from Safari requests. You use a containing app to contain and deliver a Content Blocker on the App Store.

- Aug 30, 2020 Control your web browsing experience with Roadblock, a powerful content blocker for Safari on macOS and iOS. Roadblock blocks annoying and unwanted content, protects your privacy and security, improves webpage load time, and reduces browsing data usage. Roadblock is available for Mac, iPhone, and iPad.

Global usage

95% + 3.76% = 98.76%

Declares a constant with block level scope

IE

- 5.5 - 10: Not supported

- 11: Partial support

Edge

/iphone-ad-blocking-5bd0d54dc9e77c005103306a.jpg)

- 12 - 87: Supported

- 88: Supported

Firefox

- 2 - 12: Partial support

- 13 - 35: Partial support

- 36 - 84: Supported

- 85: Supported

- 86 - 87: Supported

Chrome

- 4 - 20: Partial support

- 21 - 40: Partial support

- 41 - 48: Partial support

- 49 - 87: Supported

- 88: Supported

- 89 - 91: Supported

Safari

- 3.1 - 5: Partial support

- 5.1 - 9.1: Partial support

- 10 - 13.1: Supported

- 14: Supported

- TP: Supported

Opera

- 9 - 9.6: Not supported

- 10 - 11.5: Partial support

- 11.6 - 12.1: Partial support

- 15 - 27: Partial support

- 28 - 35: Partial support

- 36 - 72: Supported

- 73: Supported

iOS Safari

- 3.2 - 4.3: Partial support

- 5 - 9.3: Partial support

- 10 - 13.7: Supported

- 14: Supported

Opera Mini

- all: Partial support

Android Browser

- 2.1 - 2.2: Support unknown

- 2.3: Partial support

- 3 - 4.4.4: Partial support

- 81: Supported

Opera Mobile

Roadblock 1 5 9 – Content Blocker Safari Settings

- 10 - 11.5: Partial support

- 12 - 12.1: Partial support

- 59: Supported

Chrome for Android

- 88: Supported

Roadblock 1 5 9 – Content Blocker Safari Yahoo

Firefox for Android

- 85: Supported

UC Browser for Android

- 12.12: Supported

Samsung Internet

- 4: Partial support

- 5 - 12.0: Supported

- 13.0: Supported

QQ Browser

- 10.4: Supported

Baidu Browser

- 7.12: Partial support

KaiOS Browser

- 2.5: Supported

- Resources:

- MDN Web Docs - const

- Variables and Constants in ES6

ABSTRACT

The Chronic Care Model (CCM) has been shown to improve medical and psychiatric outcomes for persons with mental disorders in primary care settings, and has been proposed as a model to integrate mental health care in the patient-centered medical home under healthcare reform. However, the CCM has not been widely implemented in primary care settings, primarily because of a lack of a comprehensive reimbursement strategy to compensate providers for day-to-day provision of its core components, including care management and provider decision support. Drawing upon the existing literature and regulatory guidelines, we provide a critical analysis of challenges and opportunities in reimbursing CCM components under the current fee-for-service system, and describe an emerging financial model involving bundled payments to support core CCM components to integrate mental health treatment into primary care settings. Ultimately, for the CCM to be used and sustained over time to integrate physical and mental health care, effective reimbursement models will need to be negotiated across payers and providers. Such payments should provide sufficient support for primary care providers to implement practice redesigns around core CCM components, including care management, measurement-based care, and mental health specialist consultation.

INTRODUCTION

One in four Americans suffer from mental disorders, and of those the majority also suffer from a co-occurring general medical condition, leading to substantial health care costs, impaired functioning, and premature mortality. Despite the social and economic burden experienced by people with mental disorders, only a fraction receive adequate care. The majority of persons with mental disorders never get to the mental health sector for treatment. Given that most persons with mental disorders present to primary care first, integrating mental health services into primary care is paramount.

The Chronic Care Model (CCM), is a particular type of integrated care model that has been shown to improve outcomes for persons with mental disorders,, at little to no net healthcare cost. The CCM is ideally implemented with a co-located care manager (i.e., nurse or clinical social worker) within the primary care clinic., The care manager provides counseling to patients on self-management, monitors outcomes, and consults with a mental health specialist (i.e., psychiatrist) for more complex cases. The mental health specialist is either co-located in the primary care clinic or is located off-site, with a contractual arrangement to provide consultation., The CCM is also considered the cornerstone of healthcare reform, as an operational framework for the patient-centered medical home under accountable care organizations, which seek to reward providers on improved quality and care coordination.,

- 12 - 87: Supported

- 88: Supported

Firefox

- 2 - 12: Partial support

- 13 - 35: Partial support

- 36 - 84: Supported

- 85: Supported

- 86 - 87: Supported

Chrome

- 4 - 20: Partial support

- 21 - 40: Partial support

- 41 - 48: Partial support

- 49 - 87: Supported

- 88: Supported

- 89 - 91: Supported

Safari

- 3.1 - 5: Partial support

- 5.1 - 9.1: Partial support

- 10 - 13.1: Supported

- 14: Supported

- TP: Supported

Opera

- 9 - 9.6: Not supported

- 10 - 11.5: Partial support

- 11.6 - 12.1: Partial support

- 15 - 27: Partial support

- 28 - 35: Partial support

- 36 - 72: Supported

- 73: Supported

iOS Safari

- 3.2 - 4.3: Partial support

- 5 - 9.3: Partial support

- 10 - 13.7: Supported

- 14: Supported

Opera Mini

- all: Partial support

Android Browser

- 2.1 - 2.2: Support unknown

- 2.3: Partial support

- 3 - 4.4.4: Partial support

- 81: Supported

Opera Mobile

Roadblock 1 5 9 – Content Blocker Safari Settings

- 10 - 11.5: Partial support

- 12 - 12.1: Partial support

- 59: Supported

Chrome for Android

- 88: Supported

Roadblock 1 5 9 – Content Blocker Safari Yahoo

Firefox for Android

- 85: Supported

UC Browser for Android

- 12.12: Supported

Samsung Internet

- 4: Partial support

- 5 - 12.0: Supported

- 13.0: Supported

QQ Browser

- 10.4: Supported

Baidu Browser

- 7.12: Partial support

KaiOS Browser

- 2.5: Supported

- Resources:

- MDN Web Docs - const

- Variables and Constants in ES6

ABSTRACT

The Chronic Care Model (CCM) has been shown to improve medical and psychiatric outcomes for persons with mental disorders in primary care settings, and has been proposed as a model to integrate mental health care in the patient-centered medical home under healthcare reform. However, the CCM has not been widely implemented in primary care settings, primarily because of a lack of a comprehensive reimbursement strategy to compensate providers for day-to-day provision of its core components, including care management and provider decision support. Drawing upon the existing literature and regulatory guidelines, we provide a critical analysis of challenges and opportunities in reimbursing CCM components under the current fee-for-service system, and describe an emerging financial model involving bundled payments to support core CCM components to integrate mental health treatment into primary care settings. Ultimately, for the CCM to be used and sustained over time to integrate physical and mental health care, effective reimbursement models will need to be negotiated across payers and providers. Such payments should provide sufficient support for primary care providers to implement practice redesigns around core CCM components, including care management, measurement-based care, and mental health specialist consultation.

INTRODUCTION

One in four Americans suffer from mental disorders, and of those the majority also suffer from a co-occurring general medical condition, leading to substantial health care costs, impaired functioning, and premature mortality. Despite the social and economic burden experienced by people with mental disorders, only a fraction receive adequate care. The majority of persons with mental disorders never get to the mental health sector for treatment. Given that most persons with mental disorders present to primary care first, integrating mental health services into primary care is paramount.

The Chronic Care Model (CCM), is a particular type of integrated care model that has been shown to improve outcomes for persons with mental disorders,, at little to no net healthcare cost. The CCM is ideally implemented with a co-located care manager (i.e., nurse or clinical social worker) within the primary care clinic., The care manager provides counseling to patients on self-management, monitors outcomes, and consults with a mental health specialist (i.e., psychiatrist) for more complex cases. The mental health specialist is either co-located in the primary care clinic or is located off-site, with a contractual arrangement to provide consultation., The CCM is also considered the cornerstone of healthcare reform, as an operational framework for the patient-centered medical home under accountable care organizations, which seek to reward providers on improved quality and care coordination.,

However, the CCM for mental disorders has not been widely implemented in routine practice,10, primarily because of the separation of physical and mental health services, and a lack of a reimbursement strategy. Current reimbursement codes for CCM components do not adequately compensate providers, and may not be known to providers in the first place., As a result, persons with mental disorders face the additional burden of having to go elsewhere for their mental health care, leading to duplication of services, increased costs, and overall poor outcomes.

To ultimately sustain the CCM, providers will need an effective reimbursement model for CCM components. Realistically, the reimbursement model should start with available fee-for-service codes, but should also be aligned with emerging health care reform initiatives, so that primary care providers can effectively negotiate with healthcare organizations to cover CCM costs. The goal of this paper is to provide a critical analysis of challenges in reimbursing CCM components in primary care settings under the current fee-for-service system, and discuss opportunities for developing a sustainable reimbursement model under current and evolving healthcare reform initiatives.

LIMITATIONS OF CURRENT REIMBURSEMENT STRATEGIES FOR CCM COMPONENTS

The fee-for-service (FFS) model is the predominant provider payment system for individuals with mental disorders. Table 1 provides examples of billing codes14–,19–23 under the current FFS system that could potentially be used to reimburse CCM components; notably, self-management, care management, and measurement-based care. However, current FFS codes are inadequate for reimbursing providers for the integration of guideline-based behavioral health specialist consultation, a core CCM component. Moreover, there have been no studies in which standard FFS billing practices using current payment rules lead to financial solvency of the CCM, without making the behavioral health benefit part of the general medical benefit.18

Table 1

Billing Codes Under Current Fee-For-Service for Integrated Mental Health Care Using the Chronic Care Model

| Chronic care model component description | Billing codes | Code description | Who can bill | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-management: Psychoeducation or health behavior coaching at the individual or group level or via computer or other technology | Health and Behavior Assessment/Intervention (HBAI) | For patients with primary physical illness, for management of biopsychosocial factors important to physical health problems | Non-physician mental health providers14 | Few states actively use HBAI codes, some lack corresponding relative value units15 |

| 96150, 96151, 96152, 96153 | ||||

| Psychiatric Therapeutic Procedures (Psych) | For mental and behavioral disorders16 | Psychiatrists, psychologists, clinical social workers, nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists16 | Cannot be used in primary care on same day as a physical health visit in some states | |

| 90801, 90802, 90804, 90806, 90806, 90807, 90853 (group session) 90832, 90834 | ||||

| Education and training for patient self-management (ETSM) | For individual or group self-management education | Physician and non-physician healthcare professional | Lack of evidence base for payers, not reimbursable in most states,18 | |

| 98961-98962 | ||||

| Measurement-based care: Systematic use of assessments to determine risk and outcomes | Evaluation and Management (E/M) | Evaluation and management of a new or established patient19 involving a problem-focused history, structured assessment | Physician's assistant or nurse practitioner (NP) | Other clinical nurses or social workers may not bill or provide service without sign-off from physician/NP |

| 99211, 99212, 99213, 99214, 99215, G0444, 90791, 90792 | ||||

| Care management: Coordinated services to ensure follow-up care and planning for future visits | Evaluation and Management (E/M) | Evaluation and management of a new or established patient19 involving history, examination (e.g., structured assessment) | Physician's assistant or nurse practitioner (NP) | Other clinical nurses or social workers may not bill or provide service without sign-off from physician/NP |

| 99201, 99202, 99203, 99204, 99205 | ||||

| Care Coordination (CC) | From the Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration: disease management on per member per month basis | Physicians | Not well-established or widely reimbursed; Clinical nurses or social workers may not bill or provide service without sign-off from physician | |

| G9001, G9002 | ||||

| Guideline-based behavioral health specialist consultation: Incorporation of evidence-based practice guidelines and consultations with mental health specialists | N/A | E/M may include services related to coordination of care with other providers or agencies | Currently, no codes exist to reimburse for mental health specialist consultation outside of primary care |

Current FFS billing practices are also limited because of separate public and private payers and inconsistent rules regarding who can bill for what service. This artificial separation of 'physical' and 'mental' health care, mainly through mental health carve-outs and carve-ins, prevents primary care practitioners from billing for mental health services. Location of services and insurance type also impact reimbursement. In some states, health behavior and assessment intervention codes are reimbursable at Federally Qualified Health Centers by commercial insurance and Medicare, but not by Medicaid.,19 Many public payers will not accept a physical and mental health billing code on the same day, impeding integrated care. Moreover, prior studies of the CCM for depression treatment in primary care settings used nurses or social workers as care managers, yet these professionals may not be able to use FFS billing codes for CCM components. There is great variability in what different payers (including states and health plans) will reimburse, how much they will reimburse, and the documentation and certification/licensure required. Even if billing codes are allowable, some payers may not have 'activated' them, often out of fear that the new services will increase costs without sufficient offsets.18

Under FFS, start-up costs for establishing and maintaining key CCM components are not reimbursed, including registry development, outcomes assessment tools, and contractual arrangements with mental health specialists. Many primary care clinics are operating on slim margins, and would have to spend additional time and resources to implement these components. Mental health specialists would also have to agree to block consultation time in their schedules to assist primary care providers with more complex patients. Ultimately, any long-term savings achieved through these system changes tend to go to insurance companies, but not to the medical practices.

Finally, even with available FFS codes, CCM components are difficult to implement in smaller practices. The majority (98 %) of privately insured persons with mood disorders received care from solo or small group primary care practices. Even if these providers could bill for CCM components, they may not have adequate staffing to redesign their practice to incorporate essential CCM components.

EMERGING CCM REIMBURSEMENT STRATEGIES: DIAMOND

In response to these challenges, DIAMOND (Depression Improvement Across Minnesota, Offering a New Direction)26 Dmg canvas 3 0 9 x 2. was initiated in 2008 with the goal of developing a bundled payment model to support the CCM for depression treatment in Minnesota. DIAMOND is based on a collaboration of commercial health plans, the Minnesota Department of Human Services, and medical providers within the state. Together these organizations agreed that improving depression care was a priority and that the current FFS reimbursement system was inadequate for primary care practices to support depression care management. A quality improvement organization in Minnesota, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI), brokered an agreement to implement the CCM based on a common set of shared goals and outcomes (e.g., PHQ-9 for depression).

Under DIAMOND, primary care providers implemented the CCM for depression with the incentive of receiving a negotiated monthly bundled payment from the six major insurance companies in the state for every patient needing depression care. The bundled payment was designed to include reimbursement for costs for care managers' salaries/benefits, as well as supervision time from a psychiatrist. While the primary care practices involved could not discuss the amount of reimbursement they negotiated with each insurance company due to anti-trust regulations, ICSI assessed CCM maintenance and startup costs for each practice and provided an average of these costs to the practices that could be used in their negotiations with the insurance company. The availability of this bundled payment mechanism was enough for many diverse practices to accept the burden of CCM startup costs (e.g., hiring care managers, registry development), due to the promise of at least breaking even if they recruited enough patients. The state also agreed to measure outcomes for depression centrally on a publically viewed website. As of the date of this publication, these insurance companies have continued bundled payments to support the CCM, and practices are exploring ways of expanding the program to other mental health diagnoses as well as for patients with complex chronic illnesses.

LESSONS LEARNED FROM DIAMOND

Overall, DIAMOND's implementation of the depression CCM would not have been possible without the involvement of a third party (ICSI) to effectively negotiate relationships and the bundled payment mechanisms. In addition, three key lessons were learned that can inform future implementation of CCM reimbursement and sustainability strategies (Table 2).27

Table 2

Reimbursement Strategies Under Emerging Payment Structures to Promote Integrated Mental Health Care Using the Chronic Care Model Drama prototyping animation & design tool 2 0 4.

| Stage | Procedures |

|---|---|

| Background/Initiation | Work with payers in your region/state to come to consensus on the value of the Chronic Care Model (CCM) and agree on tracking key outcomes. Provide evidence of inadequate mental health treatment and costs in your region/state. If applicable, involve local chapters of national organizations including the AMA, national social workers and nurses associations, National Council of Community and Behavioral Health Care, and the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill |

| Identify the following characteristics of your care delivery environment: | |

| 1) Provider type: Who is providing the care? | |

| 2) Location of service: At what type of facility is the care being delivered? Payer: Which organization is reimbursing for the care? | |

| 3) Content of intervention: What type of intervention is being delivered? | |

| Develop an integrated care CCM toolkit for frontline providers that includes appropriate codes, outcomes measures, guidelines, self-management materials. | |

| Negotiation | Establish a working group consisting of multiple stakeholders (e.g., providers, payer representatives), get their input on what's in it for them, and based on their feedback, develop a core set of outcomes to benchmark CCM implementation: |

| Patients—improved access to MH, improved outcomes (e.g., symptoms, functioning), and improved ability to gain contact by phone for their needs | |

| Providers—improved access to mental health and backup for depressed patients who do not tend to follow through, better outcomes in state data | |

| Employers—patients back to work, productivity | |

| Insurance companies—reduced ED and hospital utilization | |

| Publicize initial effectiveness early on to stakeholders | |

| Propose a reimbursement model using existing fee-for-service mechanisms with an eye towards developing a bundled payment model. Involve a third party to help negotiate payment rates for new reimbursement models | |

| Engage in conversations with established or potential accountable care organizations in your area, and if applicable, state health care exchanges regarding the value of applying the CCM to integrate mental health and general medical care, and under parity, to make behavioral health care part of the medical care benefit package and reimbursement mechanism. Be involved in the negotiations over how these organizations will operationalize the integration of mental health services into primary care settings and how mental health providers, including nurses and clinical social workers, will be reimbursed | |

| Current Strategies: fee-for-service payment structure | Start with existing billing codes: e.g., Table 1, and reference national sources such as the State Financing Integrated Healthcare Worksheets, available at the SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions (http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/financing/billing-tools) on the use of codes |

| Contact all contracted payers to determine if and how much they reimburse for the codes identified and what documentation is needed. | |

| If payers do not reimburse for codes you think are important, consider engaging in advocacy to 'turn on' new codes and pilot the process in primary care practices, especially codes that can jump-start key CCM processes including self-management, assessment, and care management | |

| Emerging Strategies: bundled payment structure | Consider initiating a pilot program with payers to receive a payment based on how many patients fit into the integrated mental health–CCM services being delivered (e.g., DIAMOND demonstration). Bundled payments should cover start-up costs of CCM practice redesign components in primary care, including the development of a registry and measurement-based care tools |

First, participants realized that there needed to be a frank discussion of how the program benefitted multiple stakeholders. Developing the bundled payment model required a ‘what's in it for me' analysis from all members of the healthcare interaction (Table 3). DIAMOND had a steering committee that included patients, providers, insurance companies, and state representatives, who agreed on key benchmarks to measuring program success. The reimbursement plan was negotiated with an eye towards what was possible for insurance companies, and what was most likely feasible for practices to take the risk of redesign.

Table 3

Summary of Stakeholder Interests and DIAMOND Responses

| Stakeholder | 'What's in it for me' | DIAMOND efforts to address interests |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | Access to psychiatry poor, all care requires a visit, depression results poor | Patient on steering committee, testimonials, newspaper articles |

| Providers | Hard to find psychiatrist, need extra time with patients, poor outcomes on state measures | Provider satisfaction high, testimonials, improved outcomes on Minnesota Health Scores website |

| Healthcare administrators | No money for system change and no money to reimburse ongoing care coordination | Bundled payment covers maintenance costs, regulatory measures are better and state outcomes improve |

| Insurance companies | No measures to assess outcomes in most practices, cost of depression in healthcare utilization is high | Provide promise of oversight and training of providers, measures for all sites and evidence of cost savings |

| Employers | How to measure good quality care? Depression absenteeism and presentee-ism | Outcomes and training by Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) of relevant sites, state-based measures, and white paper on work offset |

| Regulatory agencies | Measurements of process but not outcome, as felt not to be possible in practice | Both process and outcome measures included and publically reported |

Second, results from DIAMOND needed to be disseminated early on in order to sustain stakeholder engagement. As a quality improvement project rather than a formal randomized study, the success or failure of DIAMOND depended on early publication of outcomes on their website, without the peer-review process. Initial results showed better outcomes at clinics where DIAMOND models were integrated into practice, and kept the health plans and providers enthusiastic and engaged in the initiative.

Third, the CCM needed to show a return on investment beyond clinical outcomes, notably employee productivity. Employers contracting with the health plans involved in the initiative needed to see how the program impacted their bottom line (employee productivity and costs). Hence, ICSI published a white paper highlighting the impact of the CCM on increased work productivity. In response to the white paper, a subsequent study was conducted showing that even mild depression was associated with significant productivity loss (including absences and impaired functioning at work), thus making a stronger business case for depression treatment among employers.

In addition, there were also unexpected findings based on the initial implementation of DIAMOND. In contrast to chronic medical illnesses such as diabetes, the introduction of a care coordination plan for depression was not as natural for many primary care clinics. Adobe premiere pro cc 2019 13 1 14. Despite wide dissemination of depression practice guidelines, primary care providers still requested specific tools to implement the CCM in their routine practice. Based on a survey when DIAMOND was initially implemented, many providers desired user-friendly tools to incorporate depression management into their practice without losing efficiencies (e.g., incorporation of pocket guidelines, standard depression diagnostic codes, self-management materials into routine workflows). Subsequently, these tools had to be developed during the DIAMOND initiative because they were not routinely available.

In addition, primary care practices realized that the bundled payments did not cover all of their additional start-up costs to implement the depression CCM. Additional start-up costs, such as building workflows to incorporate depression measurement-based care, specialist consultation, and care managers' time in updating clinical registries, will need to be considered in future reimbursement models. One way to pay for these added costs would be to share any potential savings from reduced emergency department or hospital visits promised from the CCM with primary care practices as well as insurance companies.

SUSTAINABLE REIMBURSEMENT MODELS FOR CCM

Bundled payment strategies similar to DIAMOND have the potential to be adopted under emerging health care reform initiatives such as accountable care organizations (ACOs). Hence, it will be vital to implement a multilevel strategy to promote a sustainable CCM reimbursement model. Table 2 provides key steps for establishing a sustainable CCM reimbursement plan for primary care settings based on the lessons learned from DIAMOND.,,–32 While these steps towards a sustainable CCM reimbursement model may be daunting, evolving healthcare reform initiatives could allow for opportunities to incorporate CCM reimbursement mechanisms within state health care exchanges and Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), especially since these organizations will be benchmarked on improving coordinated care and chronic care outcomes.

Overall, the advent of healthcare reform initiatives, notably ACOs, may facilitate the uptake of the CCM through bundled payments that reward quality rather than volume. Hence, it is vital that organizations serving primary care and mental health specialty providers who are interested in the sustainability of the CCM get involved with their state-level exchanges and accountable care organizations, to ensure that these emerging payment models are adopted to implement integrated mental health–general medical care.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 MH79994) and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Service Research and Development Service (IIR 10–340). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the VA. We would also like to acknowledge Daniel Eisenberg, PhD, Department of Health Management and Policy, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, MI, for providing helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.